Ten Steps to Boost Brain Health

Step Nine

Exercise and the Brain

By

William Clearfield, D.O.

Introduction-Get Off the Couch!

Our bodies undergo a remarkable transformation during a moderate to vigorous aerobic workout. Instead of experiencing a decline, our energies strengthen, our awareness sharpens, and our conscious mind becomes a fertile ground for dormant thoughts and ideas to come to fruition.

This intriguing phenomenon revitalizes our physical state and highlights the profound impact of exercise on preserving brain function. In this episode, we dive into the captivating connection between exercise and brain health. We explore how ‘getting off the couch’ sharpens our mental faculties, enhances overall cognitive performance, and counteracts the effects of aging on the brain.

With regular exercise, our heart strengthens, our moods and outlook on life brightens, and the ravages of chronic diseases, including diabetes, cancer, and debilitating neurologic diseases, specifically Alzheimer’s Disease and Parkinson’s Disease, diminish. (1)

Now, stop your whining. Exercise reduces the risk of neurodegenerative diseases. (2) A healthy brain is the first step towards a healthy body. (3)

An up-to-date recap of our “10 Steps to a Healthy Brain” series:

- Keep Your Blood Sugar Balanced

- Eat Healthy Fats

- Get Adequate and Restful Sleep

- Enough (but not too much) Vitamin D3 is Essential for Brain Health

- Get Your Gut In Order

- Maintain Adequate Methylation

- Balance Your Hormones

- Apply the 6 Fixes for A Healthy Heart

You’re doing great. There are just two more sessions to go. This is session 9, Exercise and the Brain. Next month, we will wrap up our series on maintaining brain health with a look at lifelong learning.

But before we dive in, as a special bonus for those of you who hate and shun exercise at all costs, I give you the words of the great Mark Twain:

“The only way to keep your health is to eat what you don’t want, drink what you don’t like, and do what you’d rather not do.” (4)

The Peril of Neurodegenerative Disease

Go ahead, dear readers, laugh. But beware. You are now on notice. Ignore Mr. Twain’s parody at your peril. Need proof? Look no further than the ravages of neurodegenerative disease, defined as the erosion of the brain’s capabilities, leading to cognitive decline, memory loss, and impaired motor functions, as their incidence has more than doubled over the past thirty years. (5)

Neurodegenerative conditions, such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases, characterized by the progressive loss and demise of nerve cells, lead to the disruption of vital neurological functions necessary for routine activities of daily living. (6) These maladies have far-reaching consequences beyond the individual affected, impacting their families and society.

In 2023, experts estimated that Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias cost the United States a staggering $345 billion. (The $345 billion includes expenses for healthcare, long-term care, and hospice services for individuals aged 65 and older with dementia.) The impact on the national economy underscores the urgent need to address neurodegenerative diseases’ profound effects. (7)

Quantifying Neurodegenerative Disease

Following a basic principle in our practice, “test, don’t guess,” we identified brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) to quantify neurodegenerative changes. BDNF supports the health and functioning of the primary neuronal cells in the brain and is involved in cognitive functions such as memory and learning, mood regulation, and neuronal (brain cell) survival. Low levels of BDNF are associated with depression, bipolar disorders, and schizophrenia. (8)

In short, high levels of BDNF = a healthy brain. Low levels of BDNF mean there is big trouble in River City. As BDNF levels are challenging to reproduce, most major laboratory companies offer an alternative, “Neurofilament Light Chain (NfL)” biomarker to assess neuronal damage from neurodegenerative diseases and sports-related concussions. (9) The NfL, easily obtained via all major national laboratory companies, is the test we use to assess BDNF.

The primary stimulator of BDNF production is exercise. Specifically, BDNF is increased significantly by aerobic exercise. (10)

Exercise as a Preventive Strategy

Exercise is a robust preventive measure against neurodegenerative diseases. (11) Regular physical activity improves blood flow to the brain, stimulates the growth of new brain cells, termed neurogenesis, and promotes the release of neuroprotective proteins, which safeguard the brain against degenerative processes. (12) The biological benefits of exercise contribute to a brain better equipped to ward off the underlying causes of neurodegenerative diseases.

Types of Exercise Beneficial for Neurodegenerative Diseases

To harness exercise’s neuroprotective benefits, it is crucial to add a mix of resistance training with activities that enhance flexibility and balance to aerobic exercises. Each type of exercise contributes uniquely to brain health, offering a holistic approach to preventive care.

A. Aerobic Exercises:

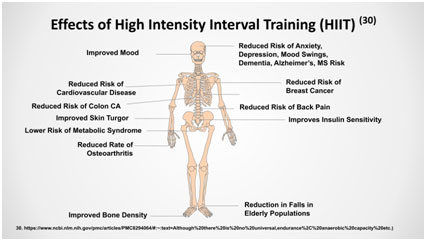

The good news is that high-intensity interval training (HIIT) is the most beneficial form of aerobic exercise instead of slogging through hours of aerobics on a treadmill or elliptical machine. (13)

HIIT consists of brief, all-out efforts followed by slightly extended rest periods. HIIT increases BDNF and improves brain function. (14)

Belonging to a gym isn’t necessary. After several simple stretches, warm up for 3-5 minutes with a moderately paced walk or jog. Then, for the next 30 seconds, hit the ground running or walking if there are orthopedic issues at your maximum speed. Time it with a stopwatch or timer. After 30 seconds, slow to a walk for 30 seconds. Then, resume your “sprint.” (15)

At first, you may be unable to do more than 1 to 2 intervals. Start low and build your interval capacity slowly.

Rinse and repeat.

You can perform HIIT by running outdoors or on a treadmill, brisk walking in a location that suits you, cycling on a bike or stationary bike, climbing stairs on a stepper machine or at home, rowing on a machine or in a waterway, doing calisthenics, or performing bodyweight exercises such as lunges, jumping jacks, squat jumps, and burpees. (16)

HIIT accelerates fat loss while improving aerobic and anaerobic endurance, brain function, and cognitive activity. (17) Of all the exercise regimens devised by mankind, HIIT is your reproducible go-to standard.

2-3 times per week for no more than thirty minutes is more than an adequate starting regimen. After eight weeks of HIIT, your fat melts away, your heart beats stronger, and your psychological well-being and executive function sharpens. (18)

B. Resistance Training: (19)

Humans do not live on aerobic activity alone. We must strengthen and move our muscles to harness exercise’s neuroprotective benefits fully.

Weight Training: Start low, go slow, and target key muscle groups. Weight training includes:

● Free weights – classic strength training tools such as dumbbells, barbells, and kettlebells.

- Medicine balls or sandbags – weighted balls or

● Weight machines – devices with adjustable seats with handles attached to weights or hydraulics.

Resistance Bands: “Giant rubber band-like” stretchy things that provide increasing resistance with increasing band thickness. Resistance bands are portable, adapt to most workouts, and provide continuous resistance throughout a movement.

Bodyweight exercises include planks, leg raises, and wall sits for core strength and stability.

C. Flexibility and Balance Exercises: (20-21)

Disciplines such as yoga enhance neurocognitive skills and improve neuronal plasticity. Tai Chi enhances physical flexibility and balance, promotes mental tranquility, and mitigates stress.

Choose Yoga styles for flexibility, balance, and mindfulness, emphasizing cognitive relaxation.

Tai Chi enhances coordination and mental focus. To enhance neurocognitive skills and improve neuronal plasticity, strive to perform fluid, continuous movements.

Recommended Exercise Duration and Intensity

A. Guidelines from Health Organizations

- World Health Organization (WHO) Recommendations: (22)

The World Health Organization advises adults to engage in at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity per week, such as brisk walking, or 75 minutes of

vigorous-intensity activities, like running. Spreading these activities throughout the week avoids prolonged periods of inactivity while helping reduce the risk of cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, and certain types of cancer.

For additional health benefits, increase aerobic physical activity to 300 minutes per week of moderate-intensity or 150 minutes of vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activities. Increased

physical activity further reduces the risk of heart disease and diabetes and helps manage weight more effectively.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Guidance: (23)

The Centers for Disease Control recommends including muscle-strengthening activities two or more days a week that target all major muscle groups (legs, hips, back, abdomen, chest, shoulders, and arms). Strength training includes lifting weights, working with resistance bands, or doing exercises that use body weight for resistance (such as push-ups and sit-ups).

The CDC recommends dividing the recommended amounts of exercise into small segments, such as 30 minutes five times per week, which is more manageable for people with busy schedules.

B. Tailoring Exercise Regimen to Individual Needs and Capabilities

- Individual Health Considerations: Adapting exercise regimes to avoid exacerbating chronic conditions like arthritis or heart disease is crucial for those with chronic conditions. (24) For example, a patient with knee arthritis might focus on swimming or cycling instead of running to minimize joint stress. We recommend the HIIT method described above to guide how often and how much aerobic activity.

- Progressive Overload: Increasing the exercise load, intensity, duration, and frequency is essential. Progressive overload continuously challenges and improves fitness levels over time. We recommend keeping time, weight, or intensity increases to 10% or less each week. (25)

C. Long-term Commitment and Lifestyle Integration

Building a Sustainable Routine: Consistency is vital in any exercise routine. Find a time of day that works best for your schedule. Some find exercising in the morning invigorates them for the day ahead. Others might be night owls, preferring to wind down the day with evening physical activity. (26)

Integrating Physical Activity into Daily Life: Beyond structured exercise, incorporating more physical activity into one’s daily life is also beneficial. Walking or biking to work, when feasible, taking the stairs instead of elevators, and incorporating short active breaks into the workday are ways to break up a sedentary daily routine. (27)

Motivation and Goal Setting: Clear and achievable goals are a powerful source of motivation for individuals. When one sets specific objectives, such as improving cardiovascular health, losing weight, or building strength, those objectives become the guiding force for one’s exercise regimen and allow one to measure progress effectively. (28)

Conclusion

With the escalating public health challenge posed by an aging population unnerved by neurodegenerative deterioration, exercise emerges as a powerful preventive strategy. Incorporating a combination of aerobic exercises, resistance training, and activities that enhance flexibility and balance into daily routines builds a robust defense against the onset and progression of cognitive decline.

Our proposed exercise proactive approach to maintaining brain health empowers the individual and presents a viable public health strategy to reduce the future impact of neurodegenerative diseases on society. (29)

References

- Bonanni R, Cariati I, Tarantino U, D’Arcangelo G, Tancredi V. Physical Exercise and Health: A Focus on Its Protective Role in Neurodegenerative J Funct Morphol Kinesiol. 2022 Apr 29;7(2):38. doi: 10.3390/jfmk7020038. PMID: 35645300; PMCID: PMC9149968.

- Santos-Lozano, , Pareja-Galeano, H., Sanchis-Gomar, F., Quindós-Rubial, M., Fiuza-Luces, C., Cristi-Montero, C., … & Lucia, A. (2020). Physical activity and Alzheimer disease: A protective association. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 95(7), 1445-1457.)

- https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/six-ways-to-boost-brainpower/#:~:text=A%20v ariety%20of%20mechanisms%20might,communication%20and%20survival%20of%20n

- https://www.quote-coyote.com/quotes/authors/t/mark-twain/quote-3412.html

- Van Schependom J, D’haeseleer Advances in Neurodegenerative Diseases. J Clin Med. 2023 Feb 21;12(5):1709. doi: 10.3390/jcm12051709. PMID: 36902495; PMCID: PMC10002914.

- Jellinger Basic mechanisms of neurodegeneration: a critical update. J Cell Mol Med. 2010 Mar;14(3):457-87. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01010.x. Epub 2010 Jan 11. PMID: 20070435; PMCID: PMC3823450.

- 2023 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2023 Apr;19(4):1598-1695. doi: 1002/alz.13016. Epub 2023 Mar 14. PMID: 36918389.

- Hwang J, Brothers RM, Castelli DM, Glowacki EM, Chen YT, Salinas MM, Kim J, Jung Y, Calvert HG. Acute high-intensity exercise-induced cognitive enhancement and brain-derived neurotrophic factor in young, healthy adults. Neurosci Lett. 2016 Sep 6;630:247-253. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2016.07.033. Epub 2016 Jul 20. PMID: 27450438.

- https://www.labcorp.com/providers/neurology/neurofilament-light-chain-test

- Mackay CP, Kuys SS, Brauer SG. The Effect of Aerobic Exercise on Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor in People with Neurological Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Neural Plast. 2017;2017:4716197. doi: 10.1155/2017/4716197. Epub 2017 Sep 19. PMID: 29057125; PMCID: PMC5625797.

- Bonanni R, Cariati I, Tarantino U, D’Arcangelo G, Tancredi V. Physical Exercise and Health: A Focus on Its Protective Role in Neurodegenerative J Funct Morphol Kinesiol. 2022 Apr 29;7(2):38. doi: 10.3390/jfmk7020038. PMID: 35645300; PMCID: PMC9149968.

- Vecchio LM, Meng Y, Xhima K, Lipsman N, Hamani C, Aubert I. The Neuroprotective Effects of Exercise: Maintaining a Healthy Brain Throughout Aging. Brain Plast. 2018 Dec 12;4(1):17-52. doi: 3233/BPL-180069. PMID: 30564545; PMCID: PMC6296262.

- Boutcher SH. High-intensity intermittent exercise and fat loss. J Obes. 2011;2011:868305. doi: 1155/2011/868305. Epub 2010 Nov 24. PMID: 21113312; PMCID: PMC2991639.

- Jiménez-Maldonado A, Rentería I, García-Suárez PC, Moncada-Jiménez J, Freire-Royes The Impact of High-Intensity Interval Training on Brain Derived Neurotrophic Factor in Brain: A Mini-Review. Front Neurosci. 2018 Nov 14;12:839. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2018.00839. PMID: 30487731; PMCID: PMC6246624.

- https://blog.nasm.org/hiit-workout-plan

- https://health.clevelandclinic.org/think-you-cant-do-high-intensity-interval-training-think-a gain

- Atakan MM, Li Y, Koşar ŞN, Turnagöl HH, Yan X. Evidence-Based Effects of High-Intensity Interval Training on Exercise Capacity and Health: A Review with Historical Perspective. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Jul 5;18(13):7201. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18137201. PMID: 34281138; PMCID: PMC8294064.

- Guo L, Chen J, Yuan The effect of HIIT on body composition, cardiovascular fitness, psychological well-being, and executive function of overweight/obese female young adults. Front Psychol. 2023 Jan 18;13:1095328. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1095328. PMID: 36743598; PMCID: PMC9891140.

- https://www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/health/healthyliving/resistance-training-health-benefit s

- Wang X, Si K, Gu W, Wang X. Mitigating effects and mechanisms of Tai Chi on mild cognitive impairment in the Front Aging Neurosci. 2023 Jan 6;14:1028822. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2022.1028822. PMID: 36760710; PMCID: PMC9906996.7-023-00732-6. Epub 2023 Jan 26. PMID: 36701005; PMCID: PMC9877502.

- https://www.uclahealth.org/news/article/new-understanding-power-yoga

- Bull FC, Al-Ansari SS, Biddle S, Borodulin K, Buman MP, Cardon G, Carty C, Chaput JP, Chastin S, Chou R, Dempsey PC, DiPietro L, Ekelund U, Firth J, Friedenreich CM, Garcia L, Gichu M, Jago R, Katzmarzyk PT, Lambert E, Leitzmann M, Milton K, Ortega FB, Ranasinghe C, Stamatakis E, Tiedemann A, Troiano RP, van der Ploeg HP, Wari V, Willumsen JF. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br J Sports Med. 2020 Dec;54(24):1451-1462. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2020-102955. PMID: 33239350; PMCID: PMC7719906.

- https://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/basics/adults/index.htm#:~:text=Physical%20activiti es%20to%20strengthen%20your%20muscles%20are,done%20in%20addition%20to%2 0your%20aerobic%20activity.

- https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/exercise-and-physical-activity/exercising-chronic-conditions#:~:text=Strengthening%20exercises%2C%20such%20as%20overhead,COPD%20(Ch ronic%20Obstructive%20Pulmonary%20Disease)

- https://blog.nasm.org/progressive-overload-explained

- https://fitness.edu.au/the-fitness-zone/making-fitness-stick-strategies-for-building-a-susta inable-workout-plan/

- https://paragonssw.com/staying-active-at-work-simple-steps-to-combat-sedentary-lifestyl e-risk/#:~:text=A:%20Absolutely.,%2C%20flexibility%2C%20and%20cardiovascular%20 health.

- chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://health.gov/sites/default/file s/2019-09/Physical_Activity_Guidelines_2nd_edition.pdf

- Okechukwu Exercise as Preventative Therapy against Neurodegenerative Diseases in Older Adults. Int J Prev Med. 2019 Oct 9;10:165. doi: 10.4103/ijpvm.IJPVM_296_19. PMID: 32133083; PMCID: PMC6826678.

- https://ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8294064/#:~:text=Although%20there%20i s%20no%20universal,endurance%2C%20anaerobic%20capacity%20etc.)